The VC Vintage Effect

Written By

/

Hany Nada

Date

/

February 12, 2026

Summary

LPs must commit for at least 20 years to realize true VC returns. The best time to invest usually feels like the worst time. This asset class rewards long-term consistency and punishes pro-cyclical behavior.

Time diversification beats point-in-time fund selection. A mediocre GP investing in a great vintage often outperforms a top GP investing in a poor one. When you zoom out, what looks like manager selection is often vintage returns in disguise.

You need both alpha and beta. Consensus exposure gets you on the field; non-consensus judgment wins the game.

The only measure that matters is realized cash: DPI. Unrealized gains are unreliable. Interim marks understate outcomes in booms and wildly exaggerates them in busts. DPI and TVPI correlate poorly.

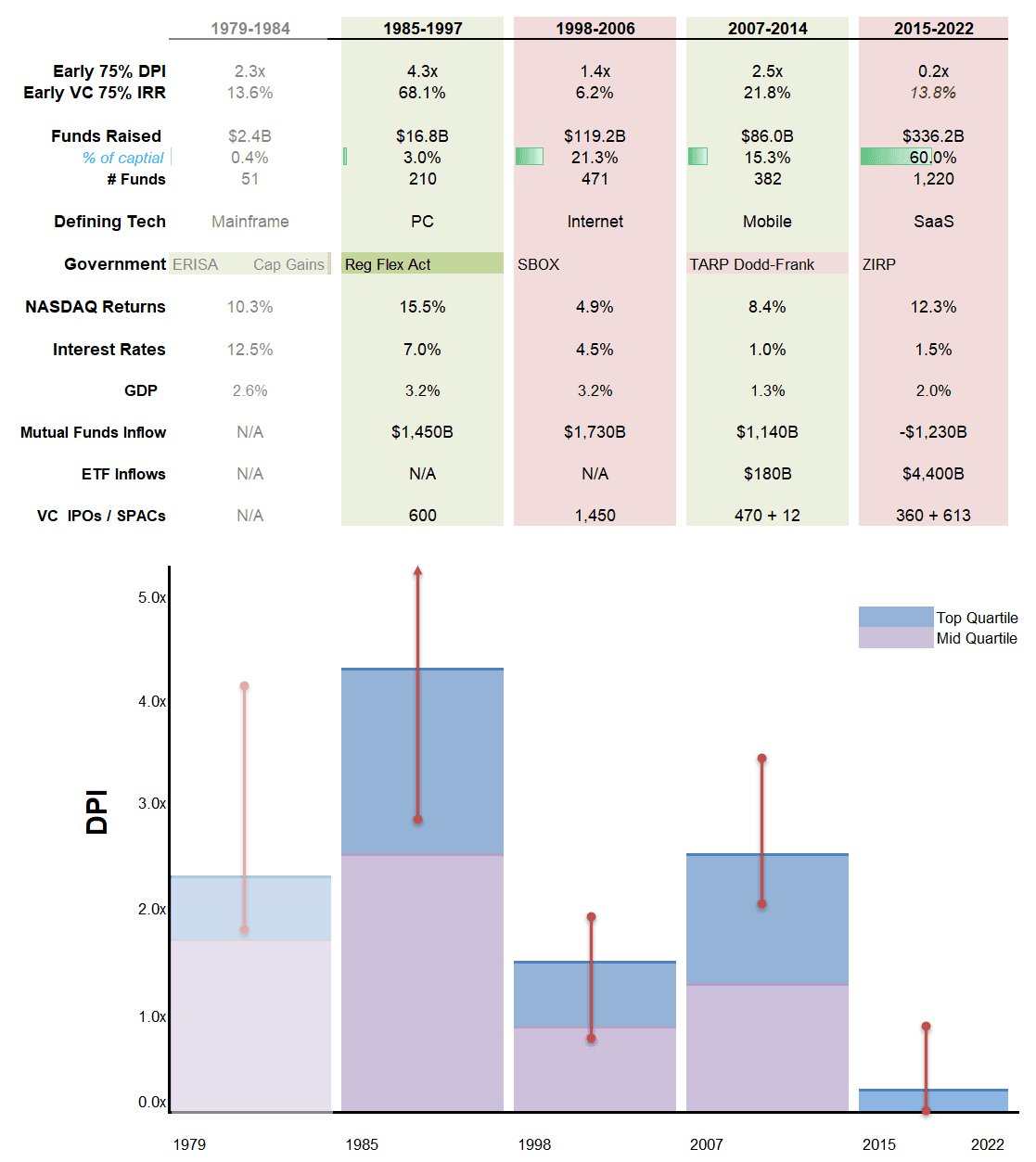

We analyzed 2,600 early-stage venture funds representing $640B deployed since 1978 [1]. The pattern is unmistakable: venture returns come in waves, shaped by sharp swings in valuations, capital inflows, and realized outcomes. The difference between entering the cycle at the right point versus the wrong one is enormous.

In boom cycles: top-quartile funds consistently return more than 2x DPI. Even median funds look strong.

In bust cycles: top-quartile funds struggle to reach 2x DPI and most managers lose LP capital.

The Momentum Game

Over the years we’ve watched LPs move in and out of venture based on headlines rather than long-term conviction. When A16Z, Thrive, GC, and Sequoia dominate the news with multibillion funds, when boards feel comfortable, when the CEO of a hot unicorn is on the cover of Forbes and when markups are abundant, VC allocations rise.

Then, when down rounds stack up, IPOs fail, three- and five-year returns turn negative, and “venture is dead” articles proliferate, those same LPs rush for the exits [2].

It is buying high and selling low in slow motion.

Investment committees reliably feel safest at the top of the cycle and most anxious at the bottom, which is exactly backward. The bottom is where the best vintages are born.

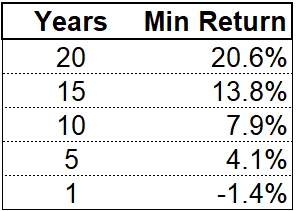

If you invested a constant dollar across any 20-year period since 1978, your minimum realized [3] net IRR would have been 20.6%. Conversely, if you were unlucky enough to invest in top-quartile funds during a five-year bust period, your IRR could fall to 4.1%. Consistent commitments across vintages are the single most important factor in long-term venture success.

The Forces That Drive Venture Cycles

1. Capital Inflows: The Original Sin

Venture capital cannot absorb sudden increases in LP commitments. Startups depend on follow‑on capital; when flows spike:

Valuations inflate. More dollars chase the same companies; a rational $20M post‑money A prints at $50M because five firms “must” own it.

Discipline erodes. Diligence windows compress; in 2021, Tiger Global deployed $12.7B across 315 companies – roughly one deal every 28 hours – an inherently thin‑diligence pace.

Exits delayed. Cheap, abundant capital defers public‑market accountability, slowing DPI.

Quality dilutes. Abundant money funds more companies, not necessarily better ones; talent gets spread thin and execution suffers. “Scarcity, not abundance, is often the true birthplace of breakthrough innovation.” [4] Too much capital destroys startup culture.

2. Expansion of Managers: When Everyone's a VC, No One Is

Abundance begets first-time funds and style drift. Some are technical operators; many are finance people chasing opportunity. New GPs pay up to “win” momentum deals, and established firms raise $1B+ and creep upmarket, pushing founders to overcapitalize.

The incentive structure breaks: fees rather than carry. When fundraising becomes easy and deployment is fast, GPs optimize for big funds and write-ups (high TVPI) rather than engineering exits. This increases near-term fees and pushes carry into the future. In the last decade, the top venture platforms have made more money on fees than they have on carry. Lastly, size and returns, a $1B fund at 2x generates far more carry for the GP than a 5x $300M fund.

3. Alpha and Beta, and the Mirage of Paper Gains

Beta is consensus exposure. It means investing mid-cycle in mobile companies in 2008-2012 or SaaS companies in 2015-2018, when it's already obvious that the category is a winner. You capture the platform shift, but so does everyone else. In boom cycles, beta generates impressive TVPIs as momentum and follow-on rounds lift valuations. In bust cycles, beta drags down returns. Beta that comes from “access” is rarely the result of real investment acumen.

Alpha is non-consensus selection: finding the companies others missed. Sequoia’s WhatsApp (everyone passed: “no revenue model, just a messaging app”). Benchmark’s Uber (everyone passed: “regulatory nightmare; taxi companies will kill it”). Lowercase’s Instagram (everyone passed: “just a photo filter; Facebook will clone it”). These outlier wins were not a question of access. They were the result of investment insight that delivered alpha.

We analyzed 2,600 early-stage funds and calculated the ratio of peak TVPI to eventual DPI once the fund was liquidated.

In boom cycles: the ratio is low (0.65x for 2007-2014 mobile). Interim TVPIs actually understated eventual returns; companies that looked fairly valued on paper later returned 5-10x+.

In bust cycles: the ratio is high (1.6x for 2015-2022 SaaS). Interim TVPIs overstated eventual returns; companies that looked strong on paper exited at a fraction of their peak valuations or did not exit at all.

High TVPI is not predictive of high DPI unless you’re in a boom. In busts, a high TVPI is often a warning sign that the fund is over-marked. One way to verify this is to use the secondary market as a reference point. Current secondary buyers are offering discounts of 30-60% to existing marks, which is a clear signal that many portfolios remain mispriced.

4. Hype Cycles and Bubbles: History Always Rhymes

Fewer than 5% of active VCs have lived through a full boom-bust cycle. This creates pattern blindness. Every new platform shift feels unprecedented: “This time is different because [mobile/social/crypto/gaming/AI].” But the anatomy of bubbles is remarkably consistent.

Phase 1: Early / Non-Consensus (Years 1-3). Technical founders, scarce capital, rational prices. The giant winners are born in this phase.

Examples: Google 1998, Facebook 2004, iPhone app developers 2008-2009, transformer-based AI companies 2019-2021.

Phase 2: Momentum / Consensus (Years 4-6). The platform is proven, mainstream adoption begins, and everyone piles in. Copycats flood the market. Prices detach from reality and valuations disconnect from fundamentals.

Examples: Pets.com 1999, Groupon 2010, DTC brands 2019, NFT platforms 2021.

Phase 3: Bust (Years 7-9). Something breaks. Fed rates rise, IPO markets close, public comps collapse, or a flagship company fails (WeWork, FTX). Follow-on capital dries up. Companies that raised at 30x revenue can't raise at 10x cash flow. Down rounds cascade. Funds that marked up portfolios aggressively take large write-downs when forced to reprice.

Phase 4: Recovery / Golden Age (Years 10-15). Scarcity returns. Survivors become category leaders with real businesses, not just compelling narratives. New founders build on a proven platform at rational valuations. These vintages generate the strongest DPI.

Examples: Amazon post-2002, Facebook and Twitter 2009-2012, Uber and Airbnb 2012-2015.

The VC timing insight: the best returns come from investing in Years 1-3 of a new platform, when it is still pre-consensus and capital is scarce. By Years 7-9, when the platform is obvious and capital is abundant, you are buying at the top.

5. Platform Shifts: Where the Real Money Is Made

Every major venture wave begins with a true technical breakthrough: a fundamental advancement that changes what is possible and opens new economic frontiers. Each platform shift creates a 10-15 year window where new business models become viable.

The pattern:

1970s: Microprocessors → PCs lowered compute costs by orders of magnitude and enabled personal computing.

1980s: Networking + GUI made computers accessible and connected.

1990s: Internet + Browser collapsed distribution costs and enabled search, e-commerce, and online marketplaces.

2007+: Mobile + Cloud put powerful computers in every pocket and produced the app economy and modern SaaS.

Today: AI + Transformers allow software to understand and generate information in ways that were not possible before, creating new workflows, tools, and business models.

AI is following this pattern step for step. ChatGPT’s debut in 2022 launched the momentum phase with horizontal applications accelerating rapidly. "Chatter about the "AI Bubble" has begun. Today, we believe the enduring value will be created in areas that remain earlier in conviction and where real-world application, not momentum, creates defensibility.

Conclusion: The LP Playbook

Commit across vintages. Don’t time; diversify time over decades.

Underwrite to DPI. Track the mark‑to‑cash gap, not just TVPI.

Diligence for investment acumen, not access. Ask for decision‑funnel stats, a regret log, pricing vs. peers, and time‑to‑DPI.

Balance beta with alpha. Own the platform shift and back non‑consensus judgment.

Fix compensation plans for LPs. i.e., time vested, match DPI multiple to a fixed “bonus” amount.

The asset class is going to shrink. It needs to shrink. Cycles will turn, stories will swell, and prices will drift, but the work doesn’t change: neutralize vintage risk by committing through the troughs, and partner with investors whose investment judgment turns TVPI into DPI. Hold them to decision‑data and mark‑to‑cash accountability, not brand or scale. With time diversification and acumen, the next golden vintages will take care of themselves.

Buy the vintage. Back the judgment. Measure by cash. Everything else is noise.

_________

[1] MSCI Burgiss Equity/Venture Capital/Early Stage from 1978-2Q2025

[2] Calpers' 'Lost Decade': The Power of Private Equity Returns

[3] We excluded unrealized results because TVPI and interim valuations have a low correlation with eventual DPI

[4] The Innovation Paradox: Why Too Much Money Kills Great Ideas